There are as many ways to convert a color image to B&W as

there are to capture the picture in the first place. In this podcast,

I explain two of my favorite methods using Photoshop CS or Elements.

You may wonder why I pick these two "traditional" methods of B&W conversion when there are new tools available in Adobe Lightroom, Apple Aperture, and the beta version of Photoshop CS3. Well, quite honestly, many photographers aren't using those new applications yet, but almost everyone has some version of Photoshop. So, we'll start with the basics, then revisit this topic again with new techniques up the road. Today, let's start with one of my favorite methods using adjustment layers.

Black & White photo of Derrick Story taken by George Jardine in Iceland.

Hue/Saturation Adjustment Layers

If you've never worked with Layers before in Photoshop, this will

be a terrific introduction to their power. I like this method for B&W

conversion, because once you have it set up, all you have to do is

move a slider back and forth until you get just the right tonal look.

It's really cool. This method works both in Photoshop CS and Elements.

Here are the steps.

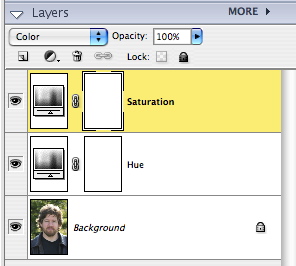

- Open the image you want to convert, and display the Layers palette

(Window > Layers).

- Create a new Hue/ Saturation Adjustment Layer (Layer > New

Adjustment Layer > Hue/Saturation). Name it "Hue" and select "Normal"

from the Mode popup menu.

- Create another new Hue/ Saturation Adjustment Layer (Layer > New

Adjustment Layer > Hue/Saturation). Name it "Saturation" and select

"Color" from the Mode popup menu.

- In the Saturation menu, move the "Saturation" slider all the way

to -100. Click "OK."

- Now, go back to your Layers palette and click once on the "Hue"

layer to select it, then double-click on the adjustment icon to open

its dialog box. Move the "Hue" slider back and forth until you get

eactly the right look you want. Click "OK."

- If you want to make any final tonal adjustments, click once on the

background layer to select it, then open the "Levels" dialog box for

final highlight, shadow, and midtone correction.

- Select "Save As" and give your file a new name, and save as a

Photoshop file with Layers perserved. That way you can always come

back and readjust the image.

- If you want to make a Jpeg copy of your B&W converted photo,

choose "Save As" again, select "Jpeg" from the Format popup menu, and

give your file another unique name. Photoshop will flatten your layers

for you and convert the image to Jpeg. You're set!

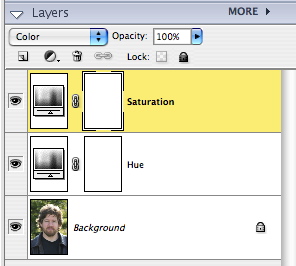

Layers Window in Photoshop Elements for above technique: Make sure the "Saturation" layer is on top of the "Hue"

layer for this technique to work properly.

Monochrome Mixer

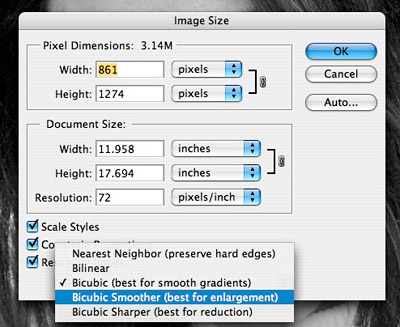

The second method works in Photoshop CS using the Channel Mixer.

This method is a bit simplier. All you have to do is open the Channel

Mixer (Image > Adjustments > Channel Mixer...). Then click the

"Monochrome" box. Set the sliders to Red=30, Green=60, Blue=10 as your

starting point. Adjust to taste from there, keeping in mind that you

want the total of your sliders to add up to 100. Then finish off your

adjustments using "Levels," and Save As a B&W version of the image.

Simple!

Feb. Photo Assignment

I also mention the February 2007 photo assignment, "Texture." Deadline for submission is Feb. 28. You can read the details on our Submissions page.

Listen to the Podcast

Now that I've piqued your curiosity, it's time to listen to today's audio show titled, "Convert to B&W." You can download the podcast here (28 minutes).

Technorati Tags:

digital photography, podcast, The Digital Story

Sponsor Notes...

Add Magic to Your Slideshows -- FotoMagico presentations are so amazing that your audience will be asking how you did it.